Mathematical Explanation

Variational Autoencoder

This article was created for those who would like to understand more about the mathematical reasoning behind a model such as VAE. For this purpose I am introducing a range of different concepts in statistics that help understand the decision-making of this paper's authors. I sum- marized only the most relevant mathematical statements for this post of each topic. To make a VAE more comprehensive I emphasized on the modeling of it and core concepts to computationally realize it. Aditionally, I used day-to-day examples and visualisations that help building an intuition. If you have any questions or suggestions regarding this topic feel free to contact me.

Table of Content

Required knowledge

The following topics are necessary to understand this article:

- Analysis 1,2 & 3

- Probability theory 1

- Basic statistics

- Basic Deep Learning

I will recap some necessary core concepts from the following topics:

- Bayesian Belief Network

- Bayesian inference

- Variational inference

- Monte Carlo Estimate

If you are keen to know more details about each topic I can suggest:

- Introduction to Mathematical Statistics by Hogg

- Mathematical Statistics by van de Geer

- Monte Carlo Methods by Kroese

Introduction

This article elaborates on relevant concepts and approaches mentioned in the paper Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes by Diederik P. Kingma, Max Welling.

To understand the architecture of a VAE, a generator, and its mathematical model, we will need to determine first the goal of such a model type and its

relationship to a discriminator.

With a discriminative model we want to make a prediction about an attribute based on various observations. Such a model tries to learn a mapping from that data

to this attribute. To do so it tries to extract features of these observations that has the highest correlation with that attribute.

Imagine, when I was a little child, I always got upset when my mom bought apples that had some brown spots. She always answered: “No, they are good! Those are just some injuries.” Sure, as if apples are like humans and could have “injuries” - you are just trying to make these cheap apples palatable, was my response back then. Indeed, my mom was right, injuries of the apples skin exposes its tissue to oxygen that turns polyphenol (a micronutrient in the apple) into melanin.

Coming back to our problem, we could collect observations, like skin color of an apple and its surface structure and so on, to make a prediction whether an apple is rotten or not. And, even though my mom was right, brown spots are usually a good indication since some infecting spores of fungi that occur in rotten apples create a brown coloration. A discriminator would be able to find that correlation, like me as a child.

Unfortunately, such a model will eliminate also apples that are healthy to consume but are just a bit damaged.

Because of those instances, a model that can learn the causal relationship is of course more precise.

To achieve that it would have to learn the generating process of decaying apples. [1]

If we abstract this case, we could say that an attribute like the level of decay is just another feature that describes an object. From that perspective every object is a state of a collection of features or call it attributes if you like.

Based on my observations and assumptions I did as a child I would have described such an apple by the following states of features:

- mainly red colored

- brown spots

- shiny skin

- decomposed

- etc.

The idea of generating realistic data can be expanded:

Let’s say we have a trained generator at hand that understands the generating process of building sentences. That means it understands that there is first an idea that is afterwards expressed in a sentence. But an idea exists within a context. So how would we incorporate such a context? An intuitive approach would be to say: Given we speak about rotten fruits and I asked “Is this apple healthy to consume?” what would be a realistic response? Such a contextual information is thereby incorporated by conditioning the input data on it.

Another important goal of training a generator is data completion. For instance, image resolution. For this purpose we need to transform the generator also into a conditional generator. It generates data depending on the state of some additional data, here a low-resolution image. [4]

Often in ML we encounter the problem of having just a very small dataset that is labelled. A generator can also help in those instances. For this purpose you let a deterministic model train parallel to the generator. The labels are then treated like features, such that the discriminative model has to predict the labels as features but also other useful descriptive features. Based on these predicted labels and features the generator has to reconstruct the original data. [5]

REMARK

Every illustration was designed by me and every mathematical statement was (re)formulated and every calculation was done by me. Obviously these statements and calculations are backed up by the sources I have mentioned in the last chapter and my mathematical background.

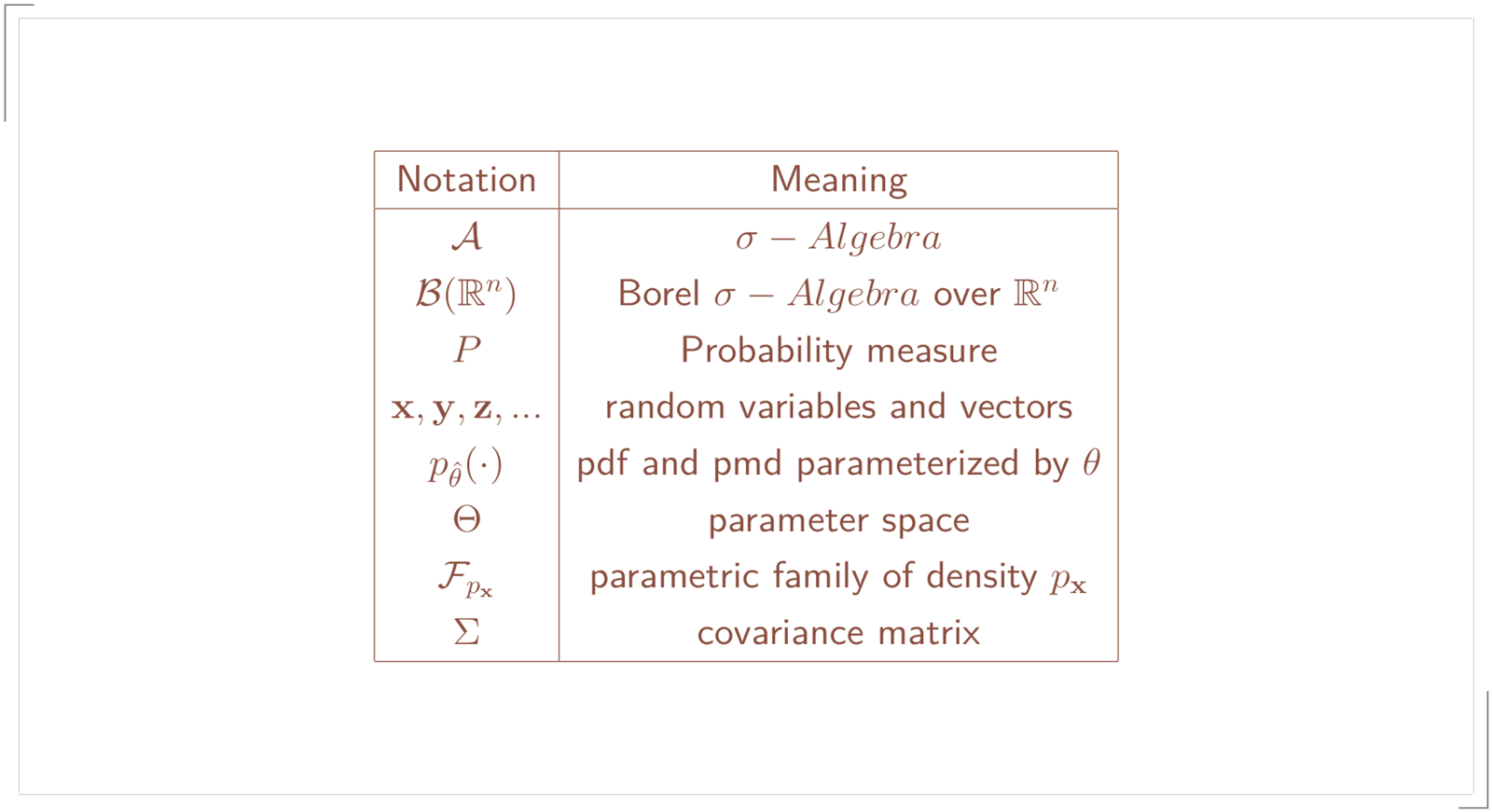

NOTATION

I usually use capital letters to denote random variables or vectors and f to denote probability density functions compared to p for probability mass functions. Since the authors of the VAE paper chose to use small letters for random variables and vectors and p for both probability density and mass function I decided to stick with that notation.

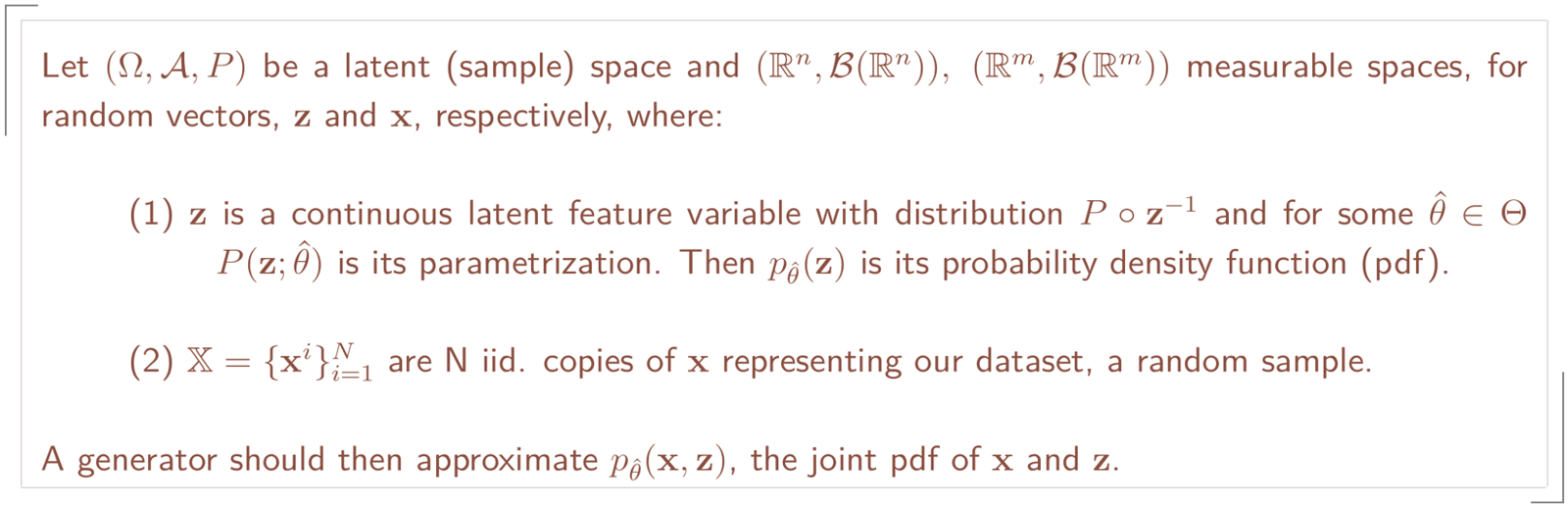

Modeling

On the left you can see a generators output for creating handwritten numbers. By varying the feature values we will obtain different results as you can see on the left image.

Let’s first formulate that mathematically:

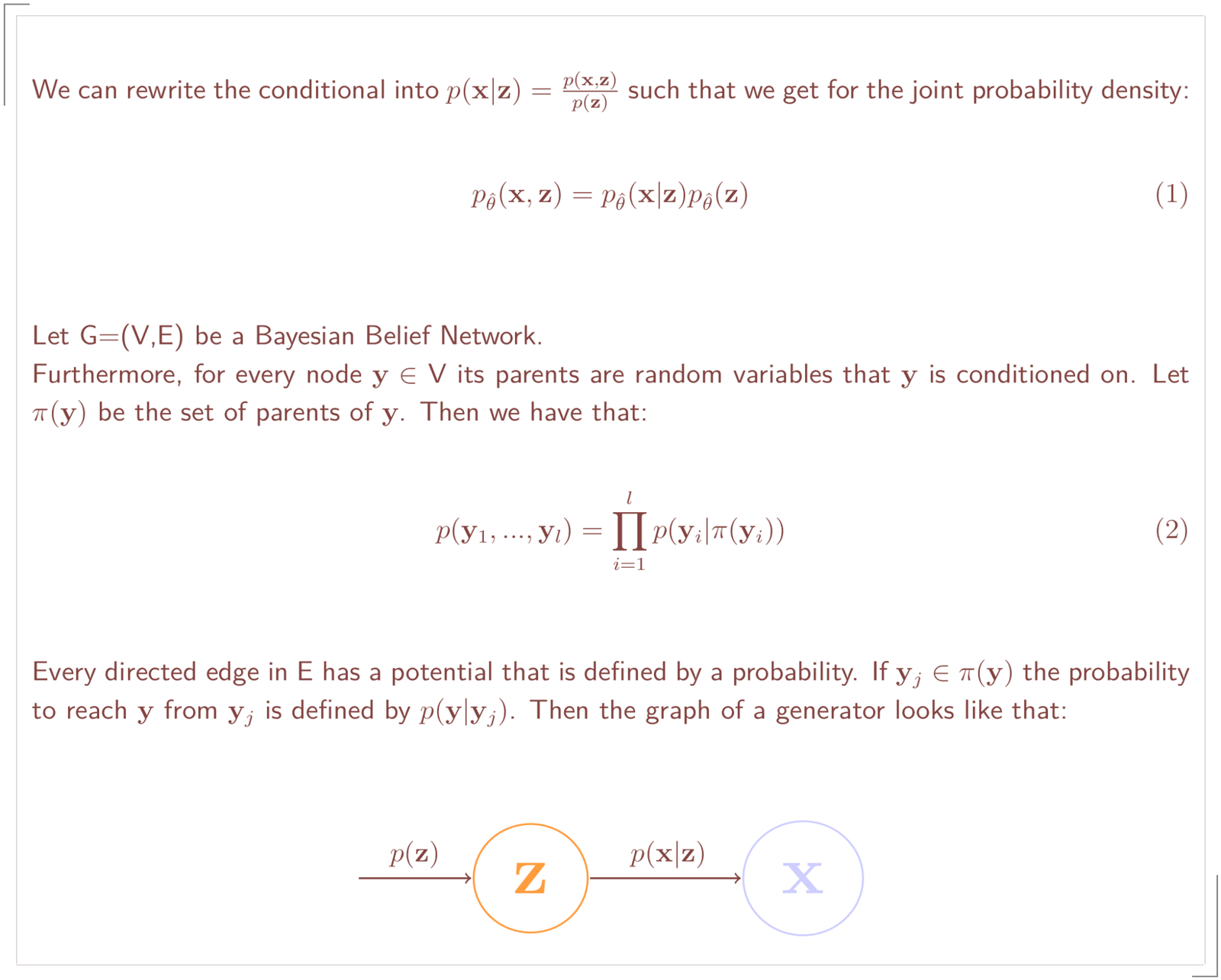

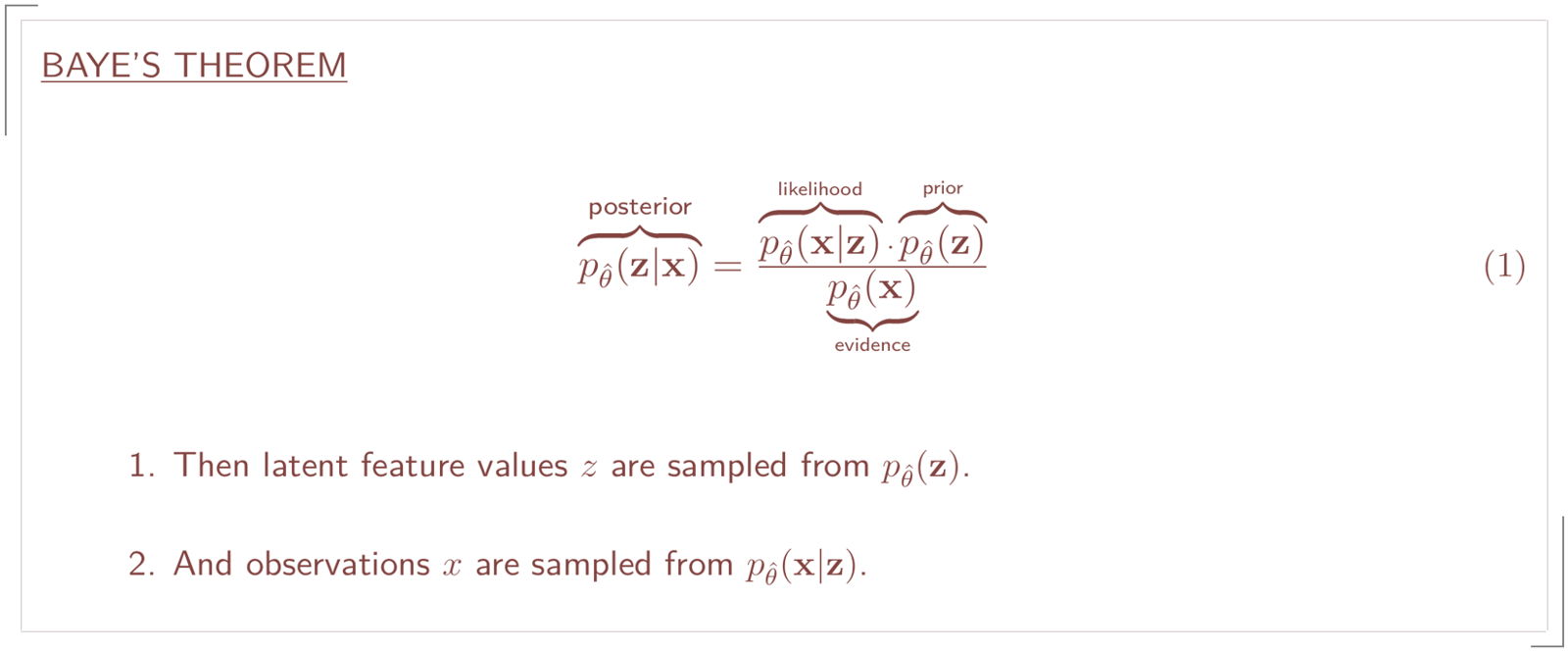

Bayesian inference

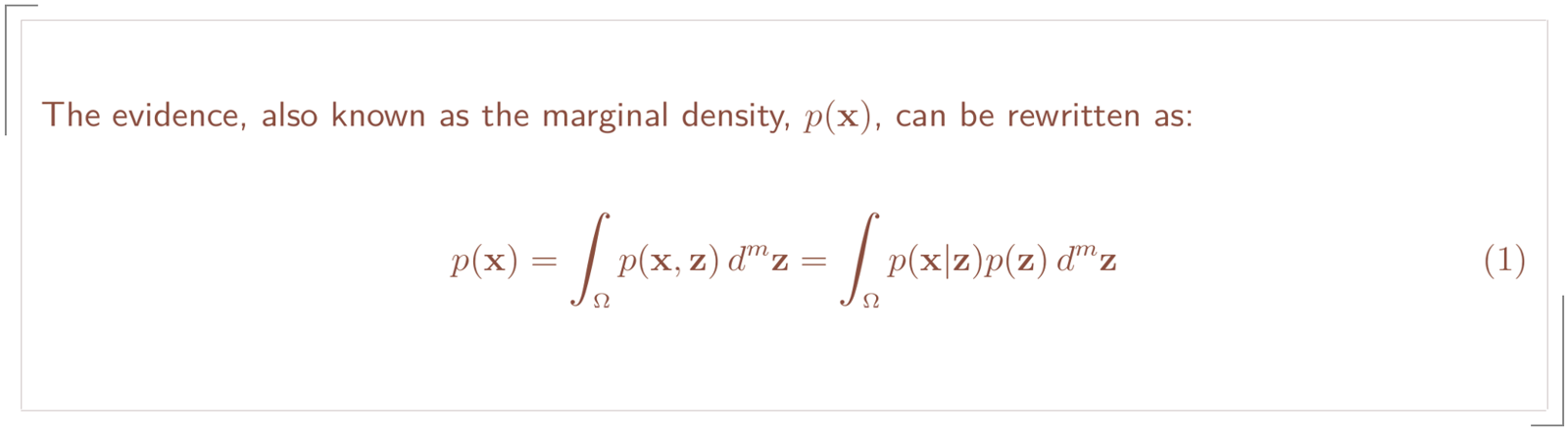

The product of the likelihood and prior is our model. At this point we are just missing the evidence, p(x). We can obtain it by marginalizing it from the joint distribution as we will later see.

This update principle will set up the architecture and mechanism of a VAE.

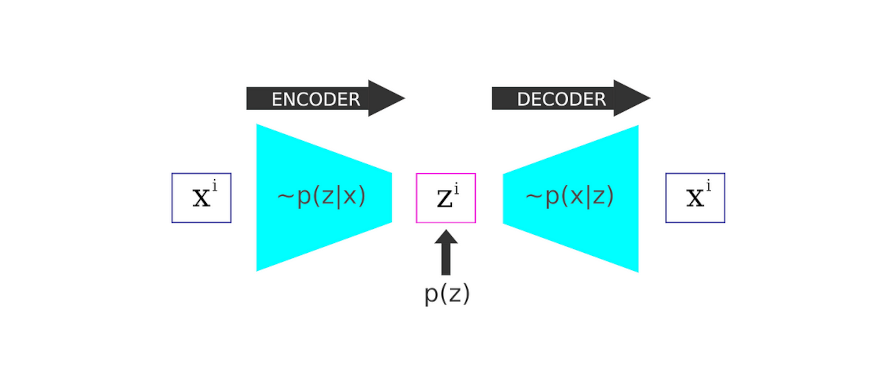

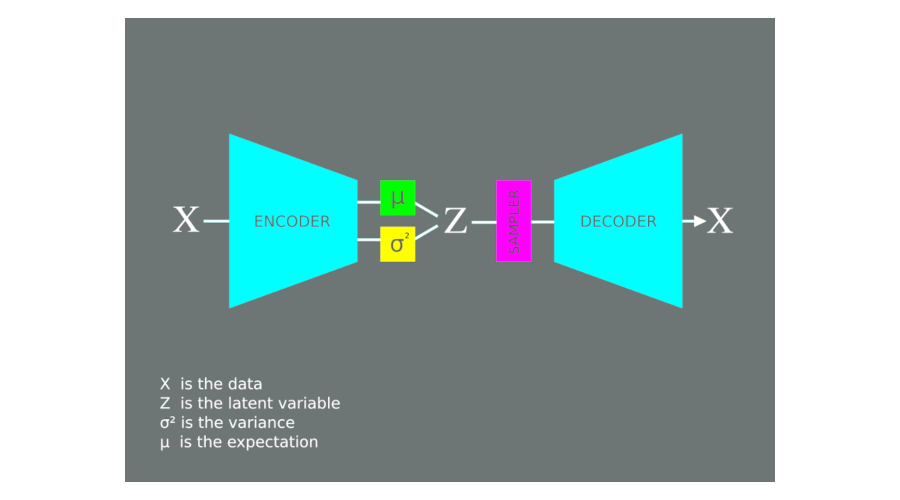

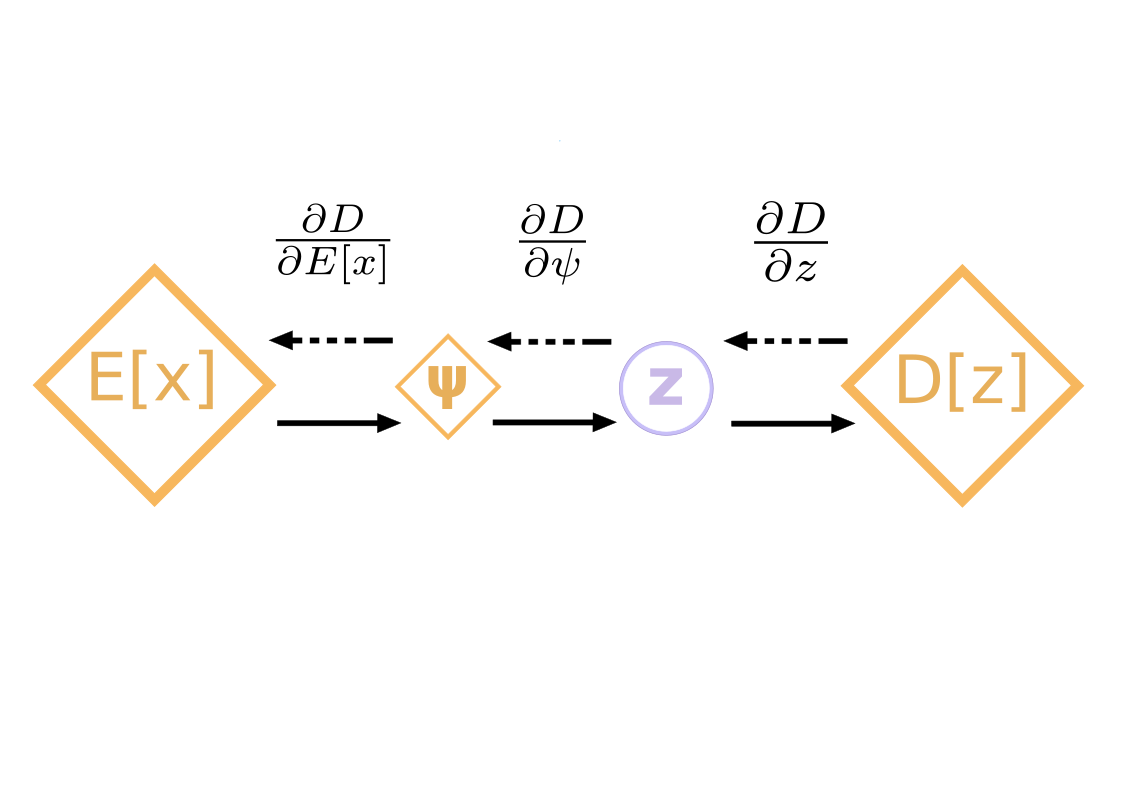

The VAE architecture

The following illustration captures this mechanism:

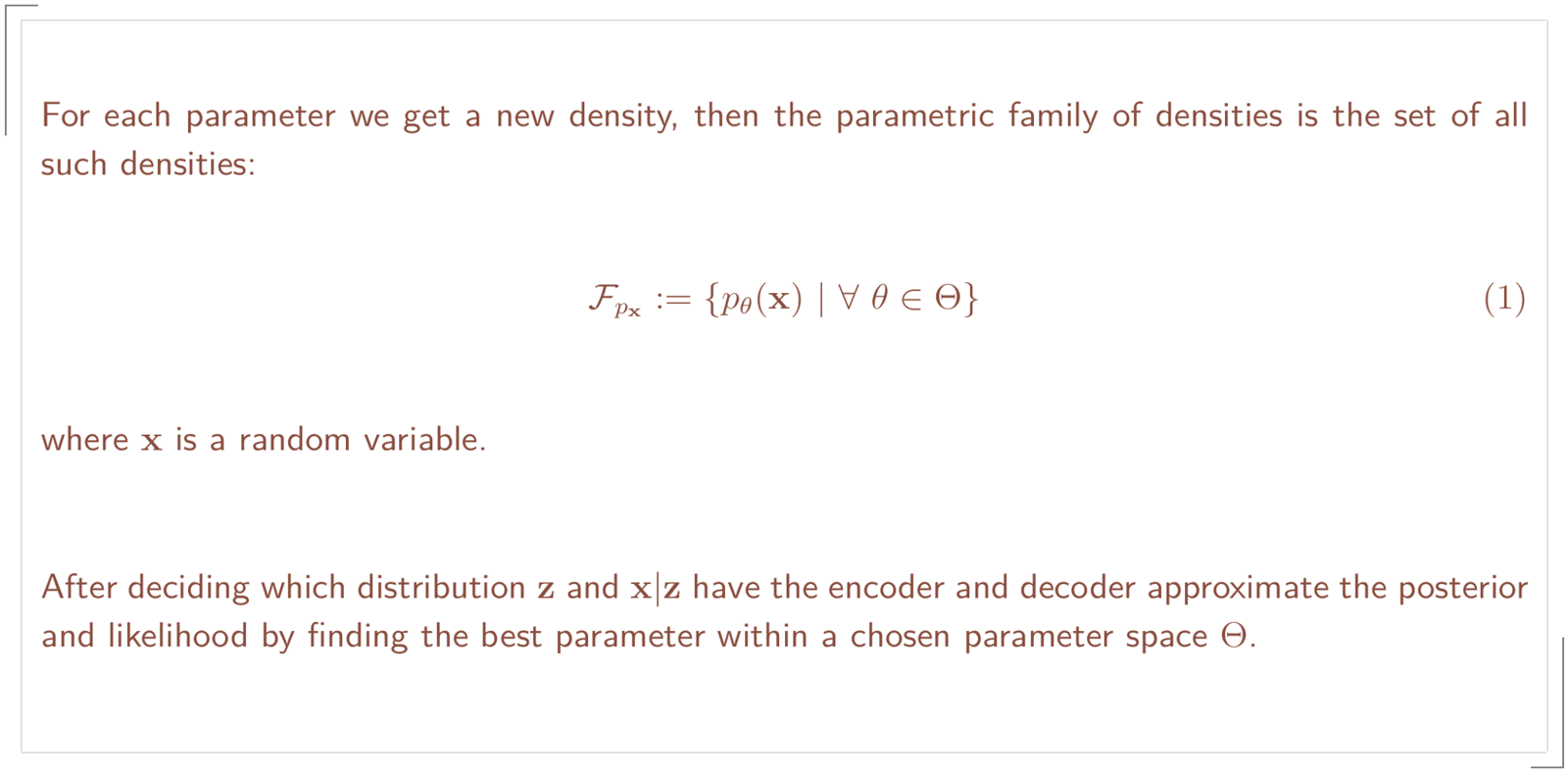

To understand the learning process for this model I will need to introduce you to the concept of a family of densities:

Intractability

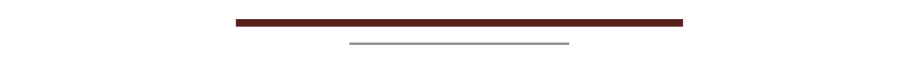

Variational inference

Equation (2) is by itself not computable in our case because it involves calculating log(p(x)). The following calculation will show that:

The Evidence Lower Bound

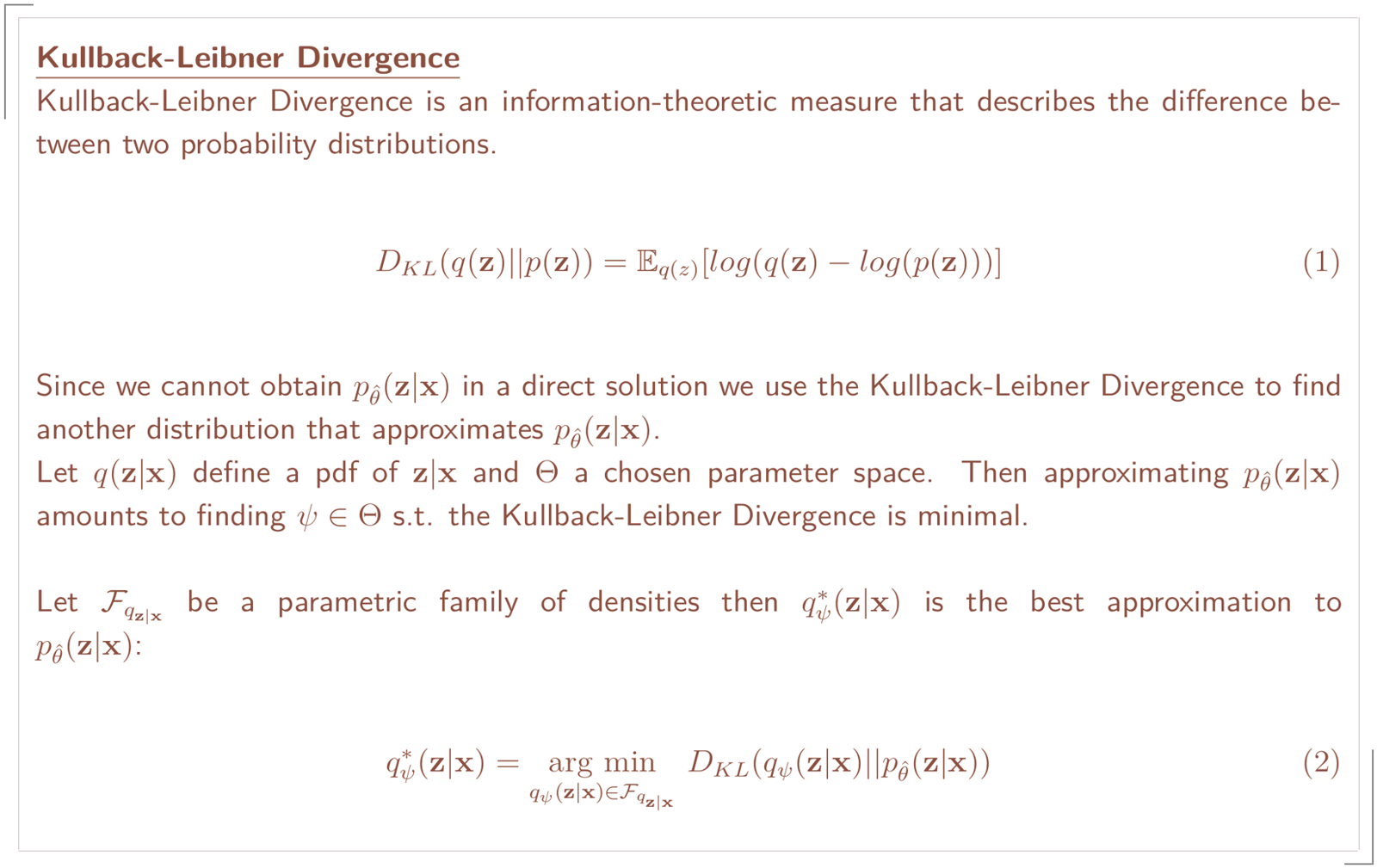

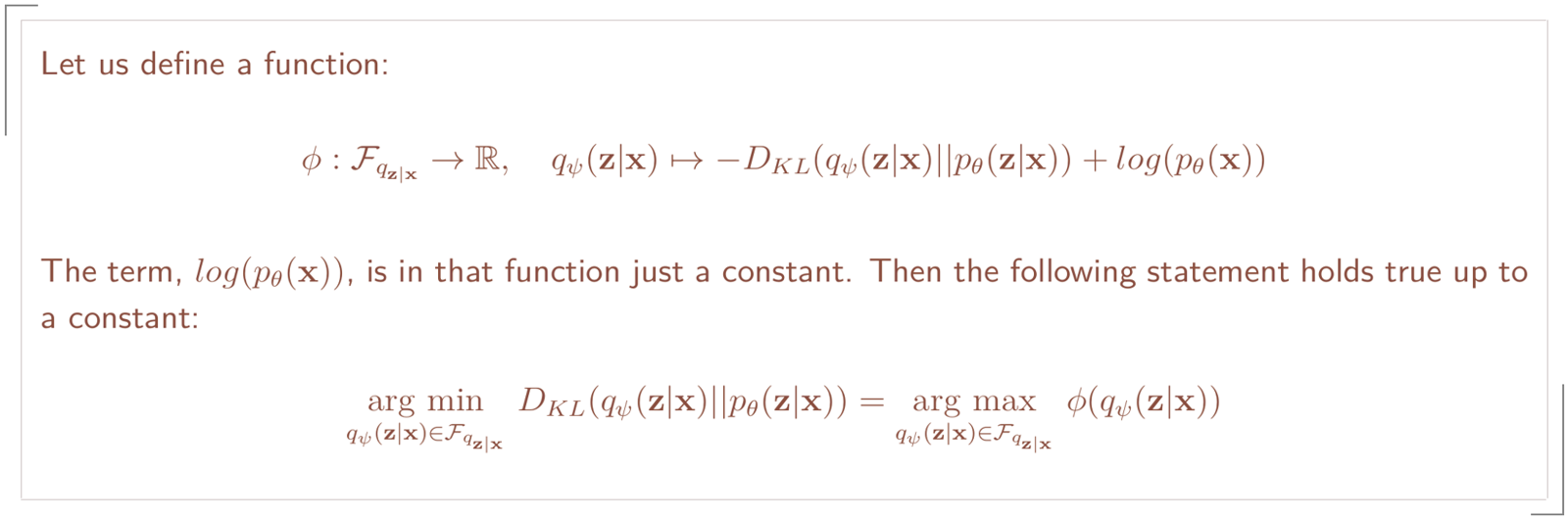

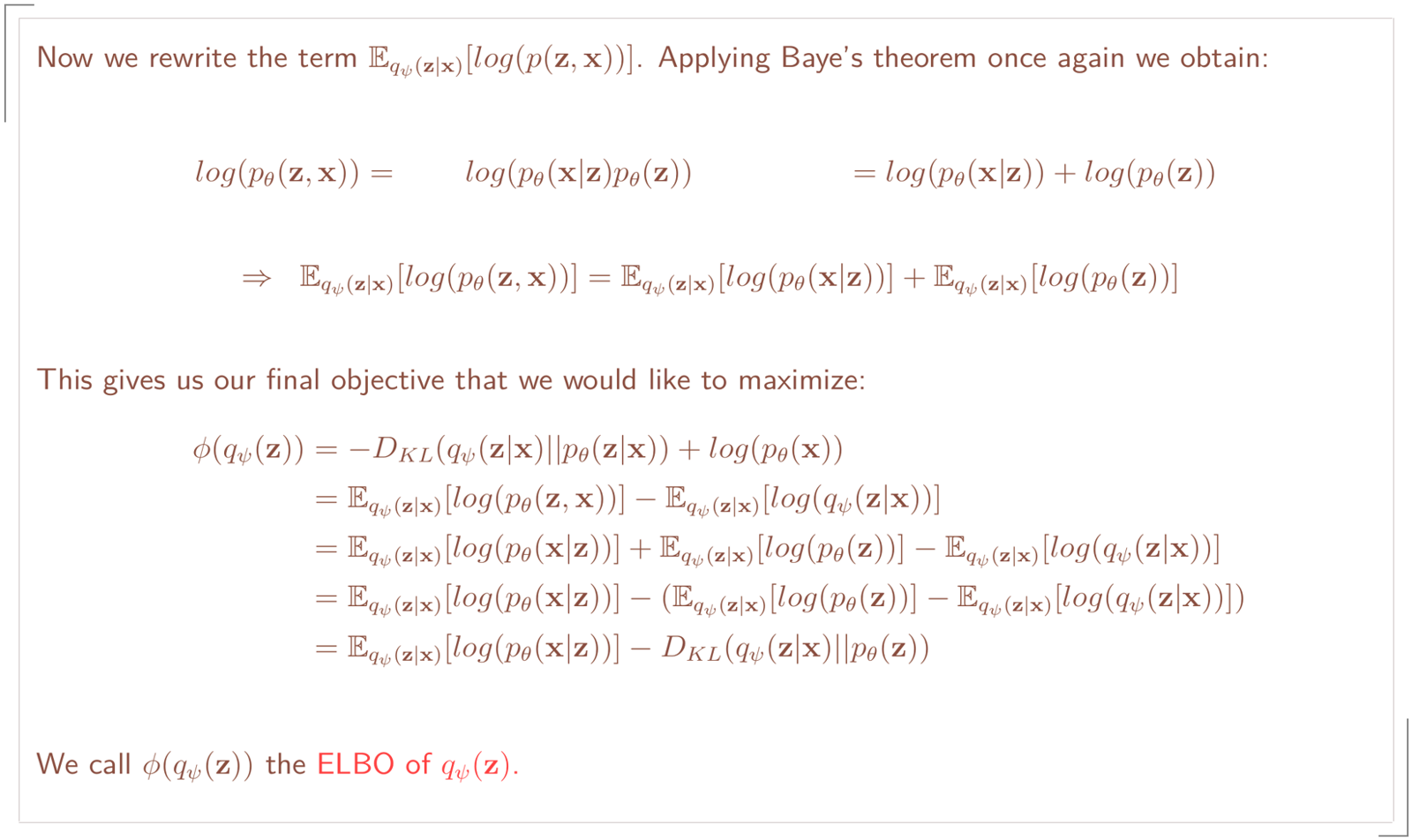

Even though the Kullback-Leibner Divergence is not computable we can use it after applying some tweaks.

By adding the log(p(x)) term to the Kullback-Leibner Divergence we eliminate log(p(x)) from our objective. With some further transformations we obtain an objective that we can use for our model.

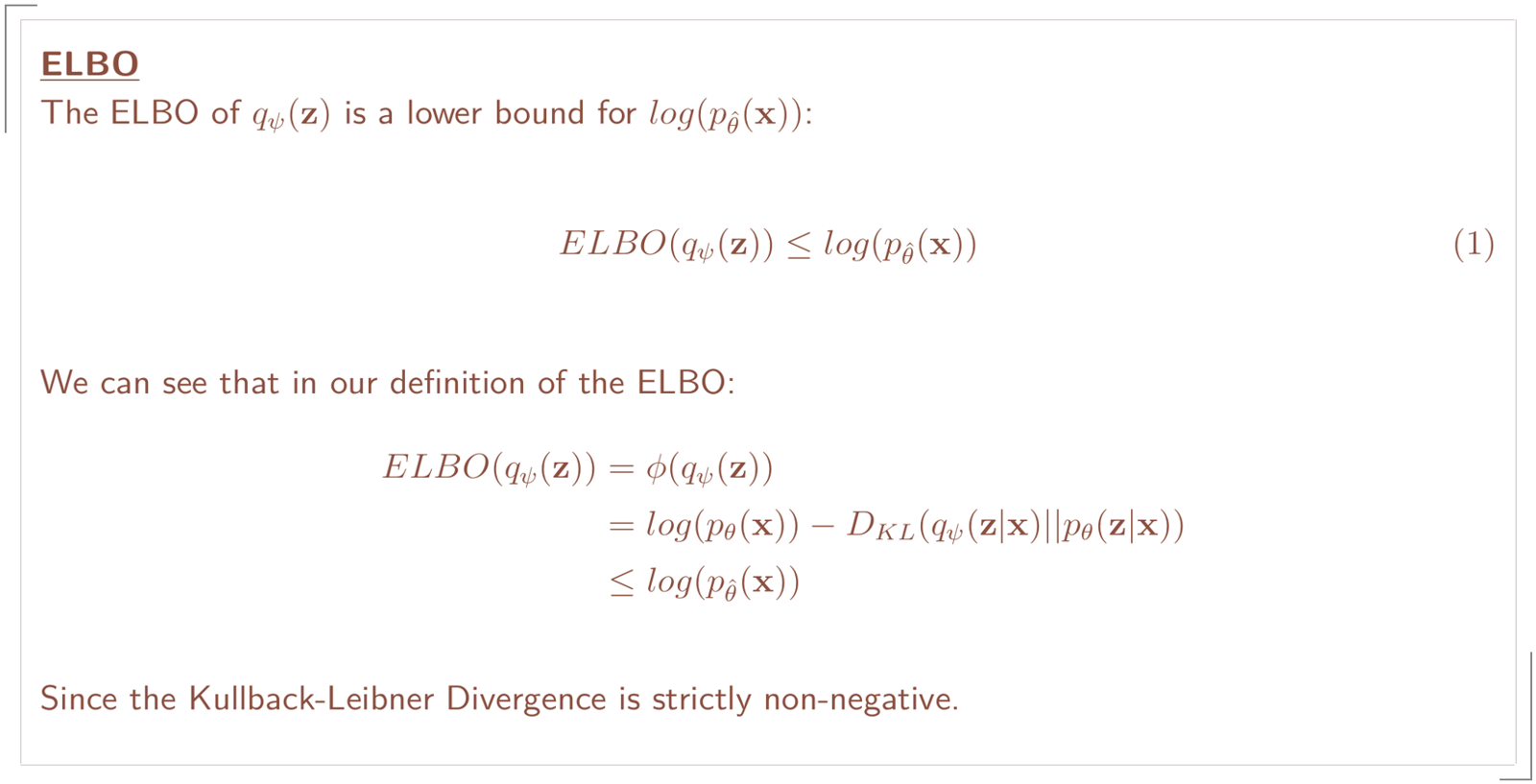

With that new expression we only have to work with the prior, likelihood and posterior. From the following property we can see the reason why it is called the evidence lower bound.

Below you can find an animated example where p is a normal density function and q a gamma density function. The gamma distribution is very flexible and, hence, useful to derive many different distributions like the chi-square, exponential and beta. The plot on top is the graph of the ELBO and below a plot of p and q with varying values for its parameters. The maximum of log(p) is zero for every density and since the ELBO is bounded from above by log(p) the ELBO is therefore bounded by zero from above.

The gradient problem

After constructing our loss function we need to find a method to train our model. Kingma and Welling intend to use stochastic gradient decent, which is a noisy estimation of the true gradient. This method requires calculating the gradient which leads us to two problems:

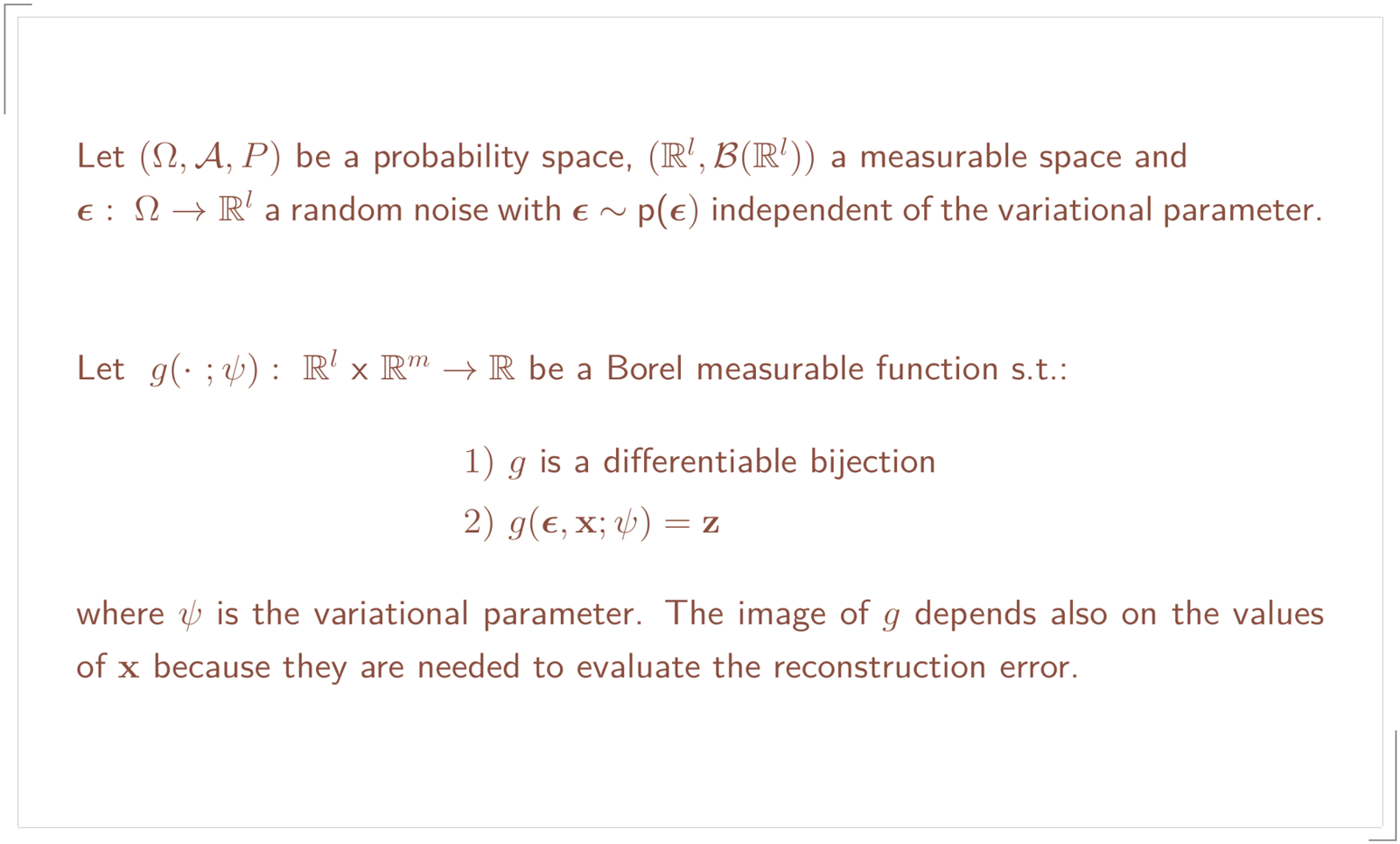

Reparameterization Trick

As you might have noticed g depends not only on the random noise, ε, but also on x. That is because we sample z from q(z|x).

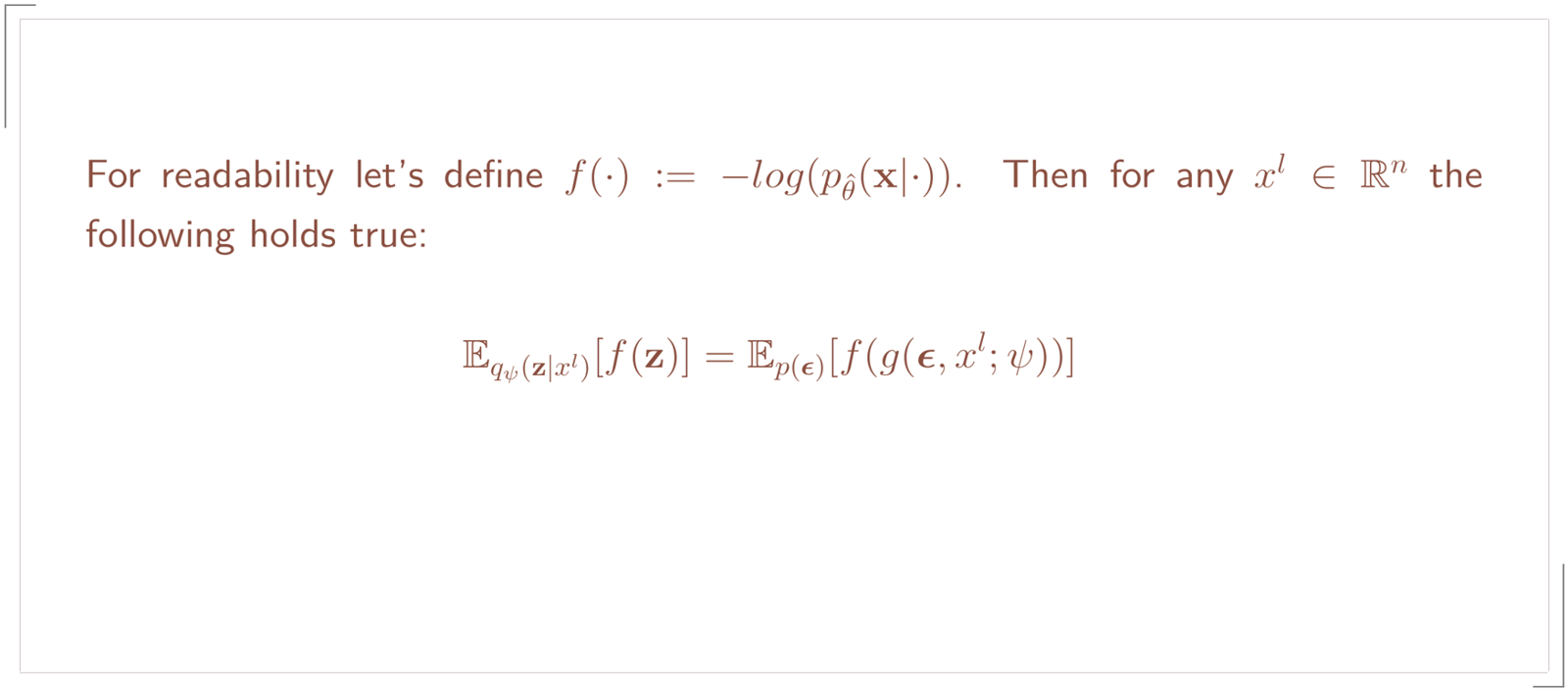

Then the Reparameterization Trick will give us the following identity:

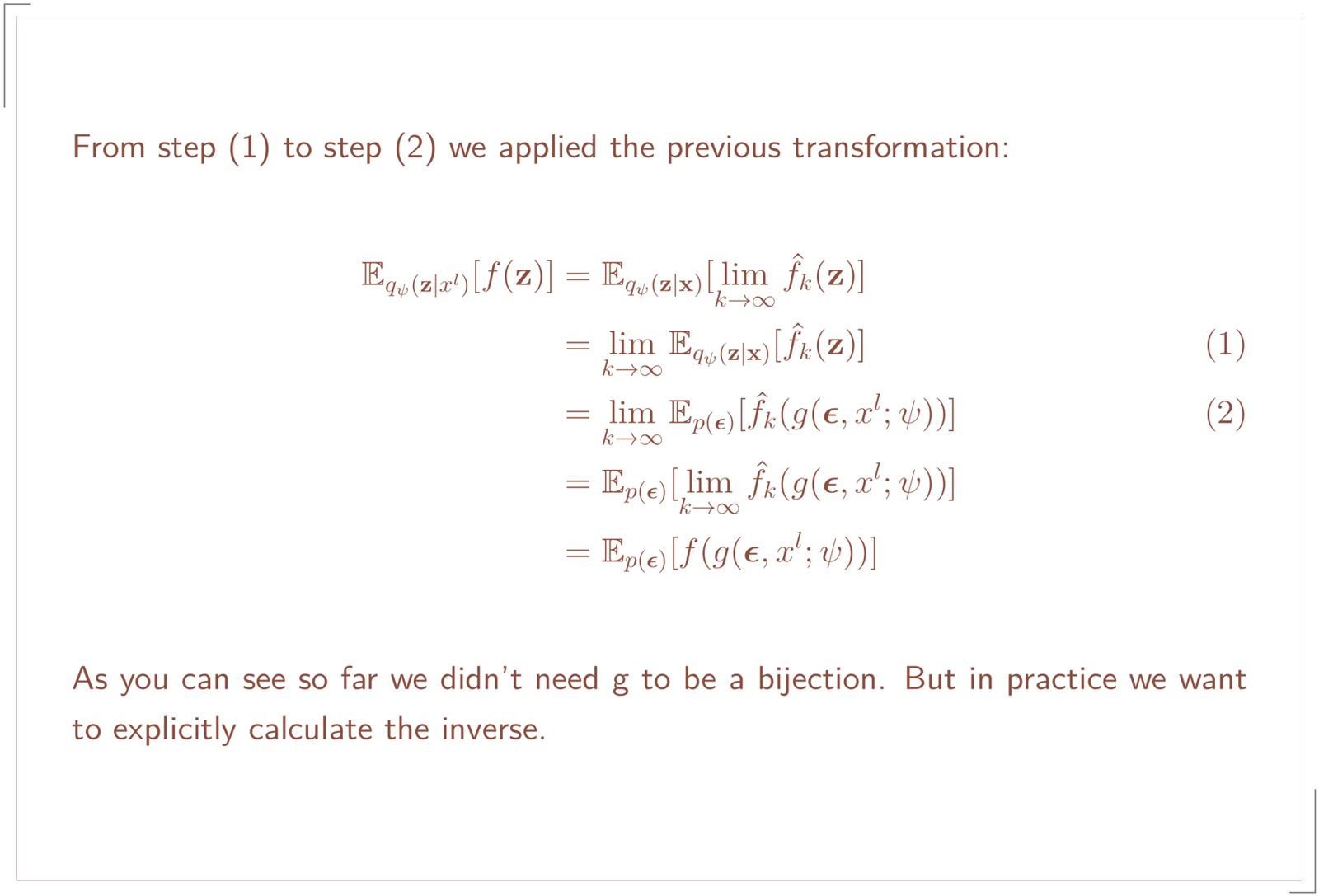

For those who know this identity can now jump the next proof. We didn’t learn that identity in probability theory 1. So here it goes: The concept of this proof is based on the transformation theorem for the expectation.

From Beppo Levi’s theorem we know for our sequence of functions we can take the integral before the limit and then by taking the limit over these sequence of elementary functions and again applying Beppo Levi we will get our identity:

Due to the linearity of the expectation we simply multiply it by -1 to obtain -f(z) = log(p(x|z)).

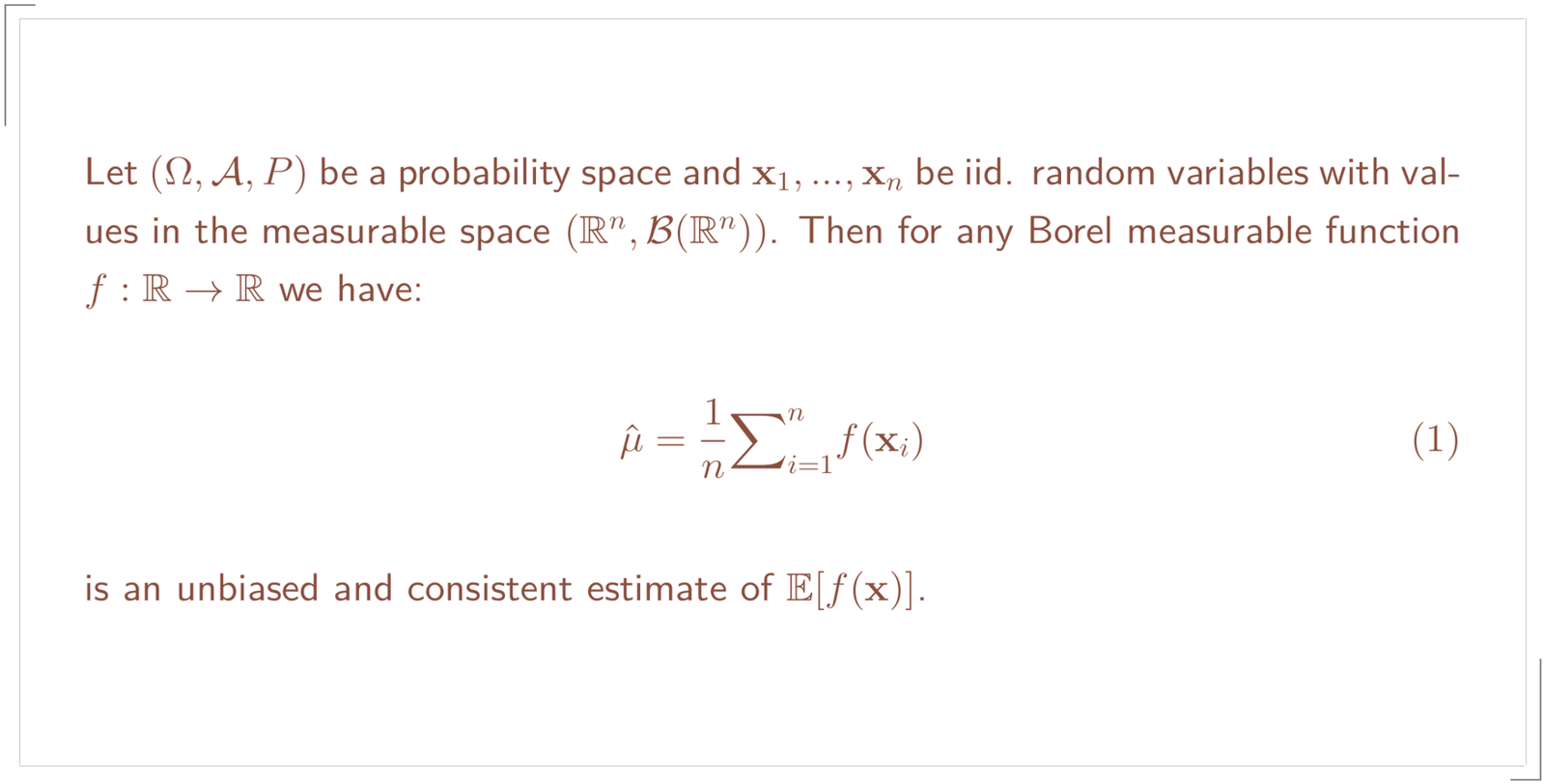

Monte Carlo Estimator

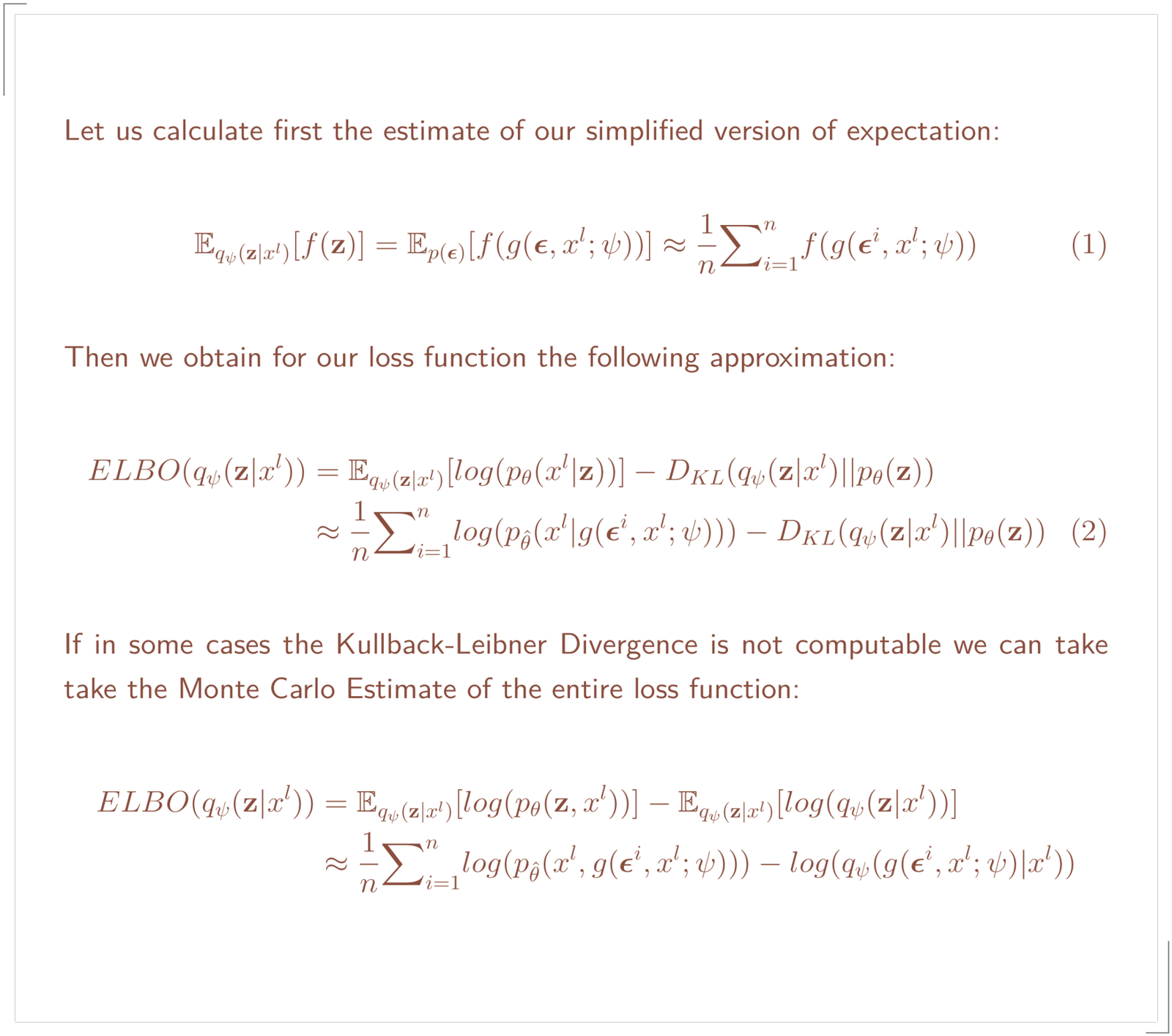

We want to use this estimate of our reparameterized expectation:

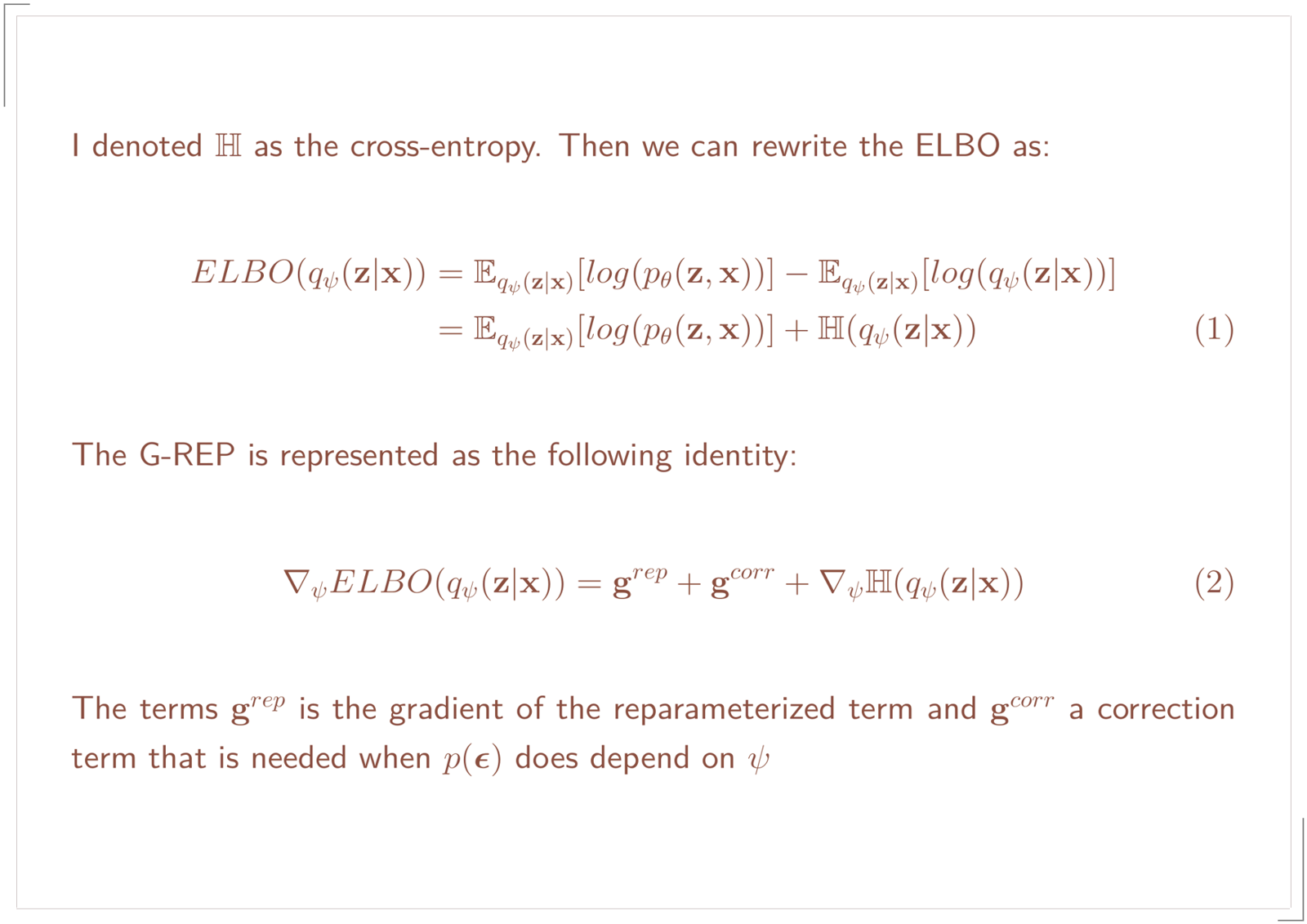

G-REP

The requirements to apply G-REP are:

- sampling from

q(z|x)can be done efficiently q(z|x)is differentiable w.r.t. z and Ψ.

Applying their generalized version yields a transformation that makes p(ε) independent of Ψ in at least its first moment.

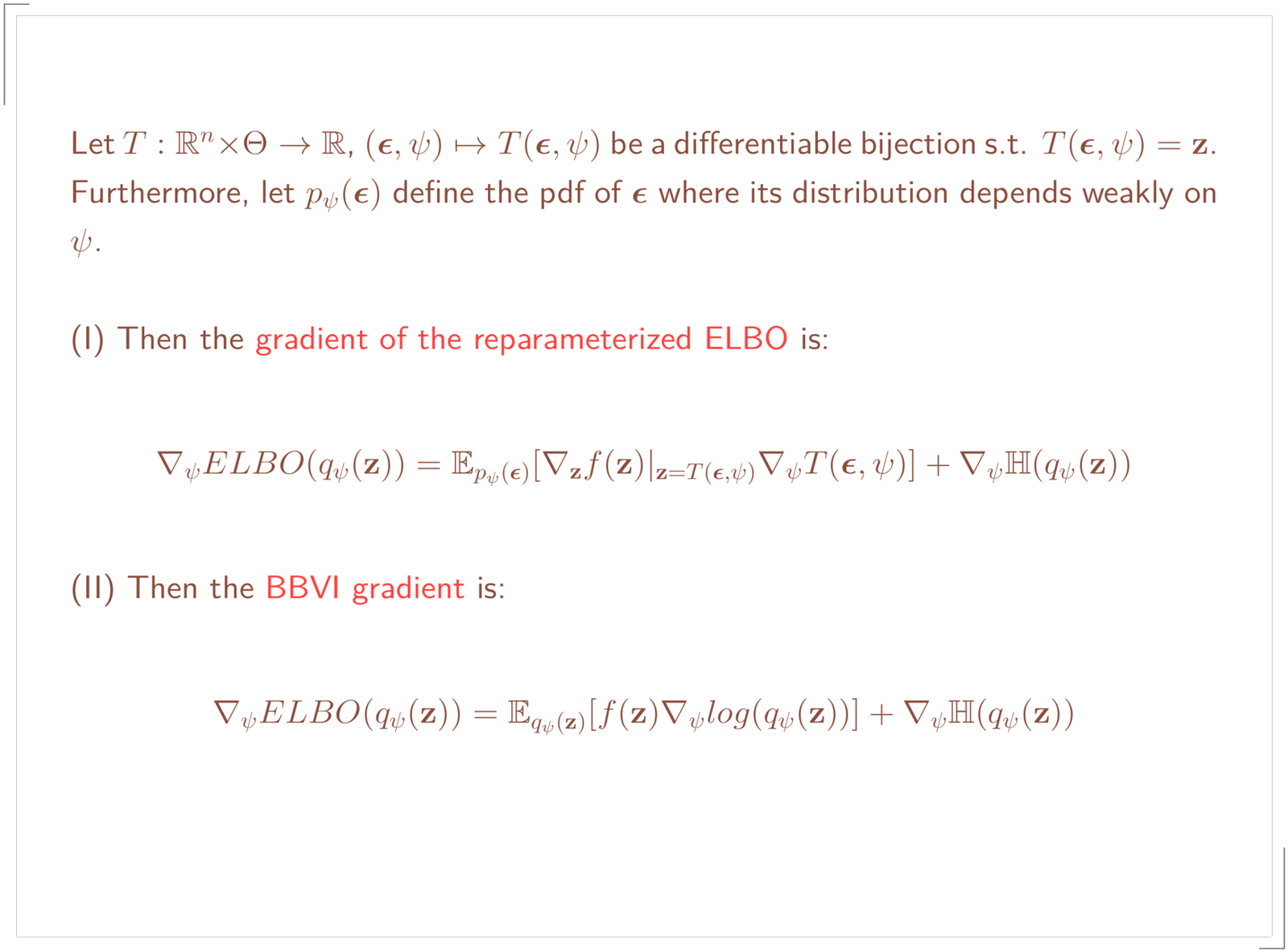

In the next section I will show you the BBVI gradient and the reparameterized gradient in comparison. Afterward I will show you how the G-REP contains both terms. For simplicity, I reduce the case to the unconditional distribution.

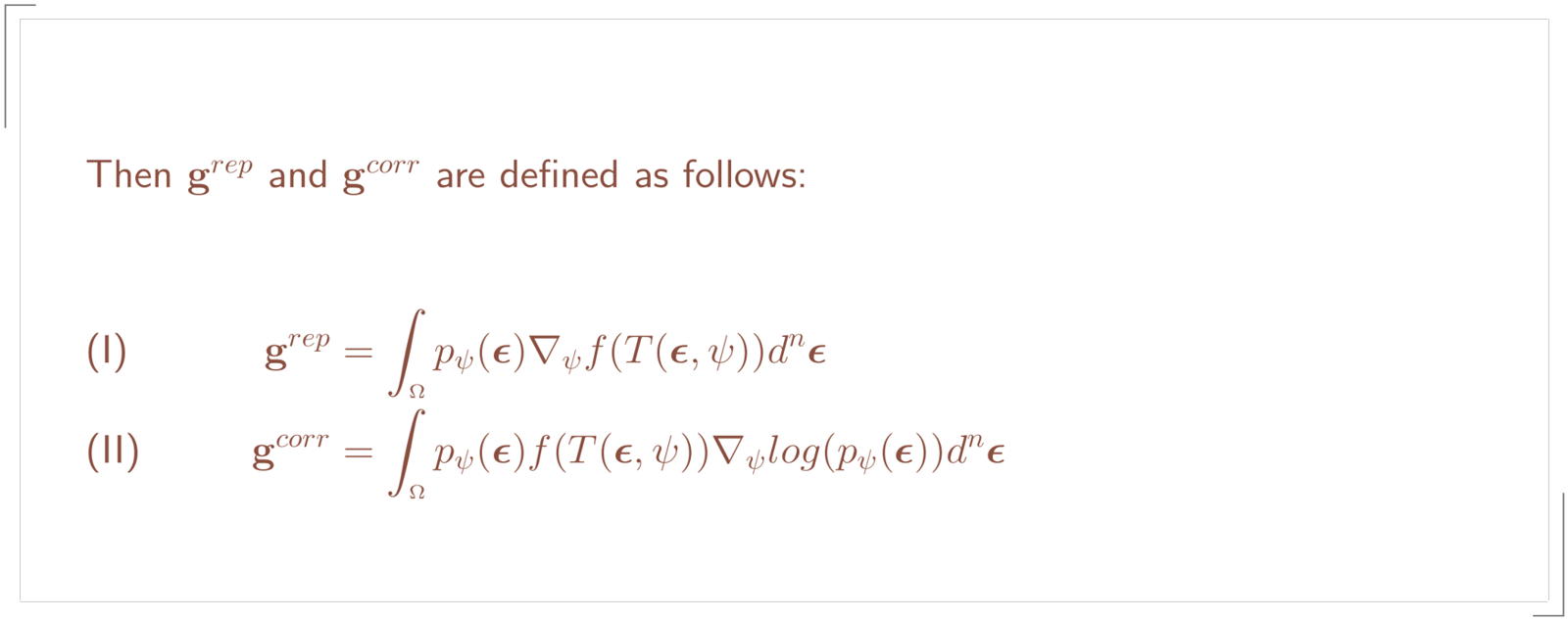

Coming back to the G-REP method it is represented by the following terms:

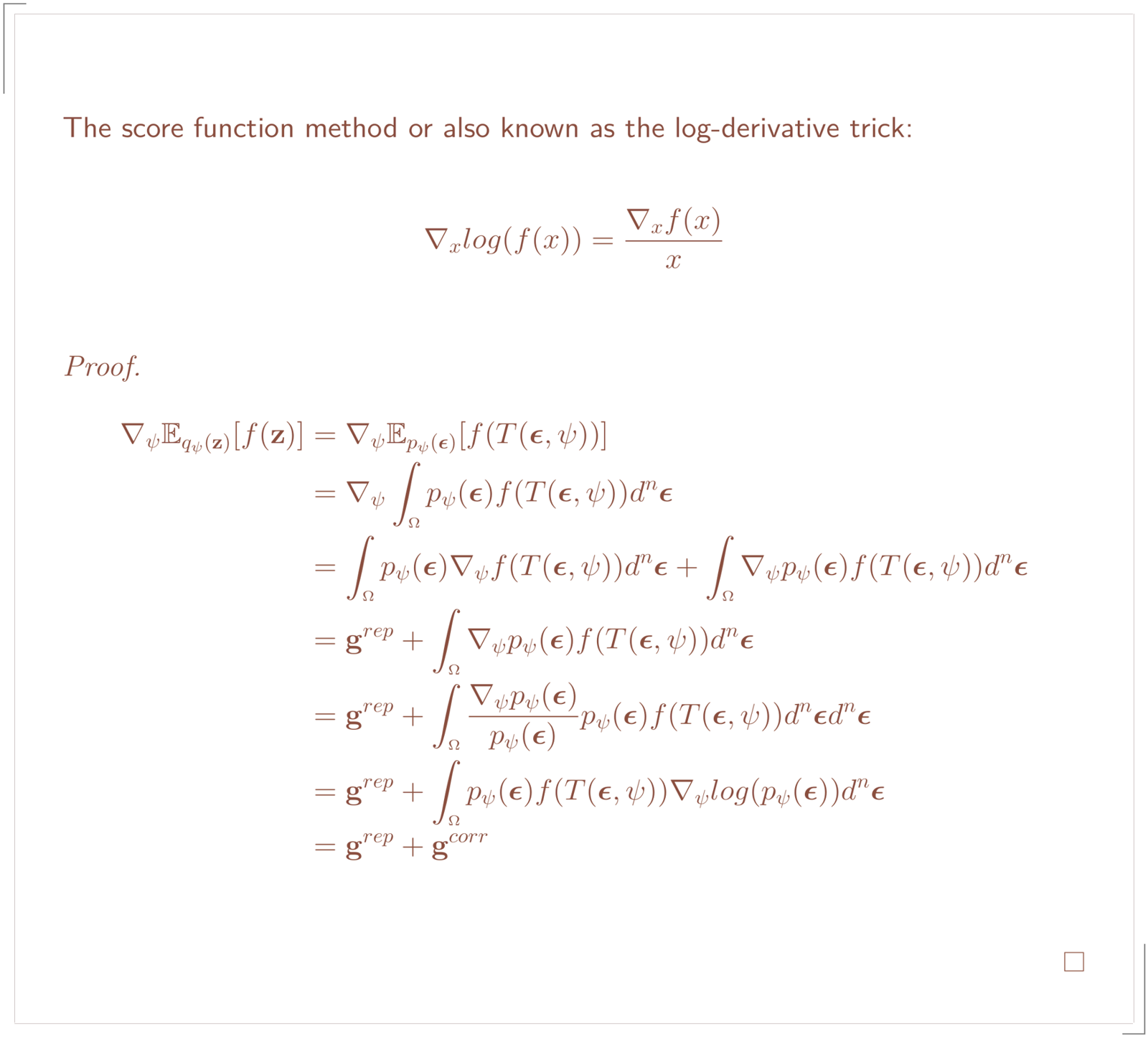

The $g^{rep}$ term is nothing else then the reparameterized expectation just writen out as an integral. By some restructuring of our objective we can derive them as a sum:

In the next section I show you how you can retrieve the BBVI gradient as well as the gradient of the reparameterized expectation:

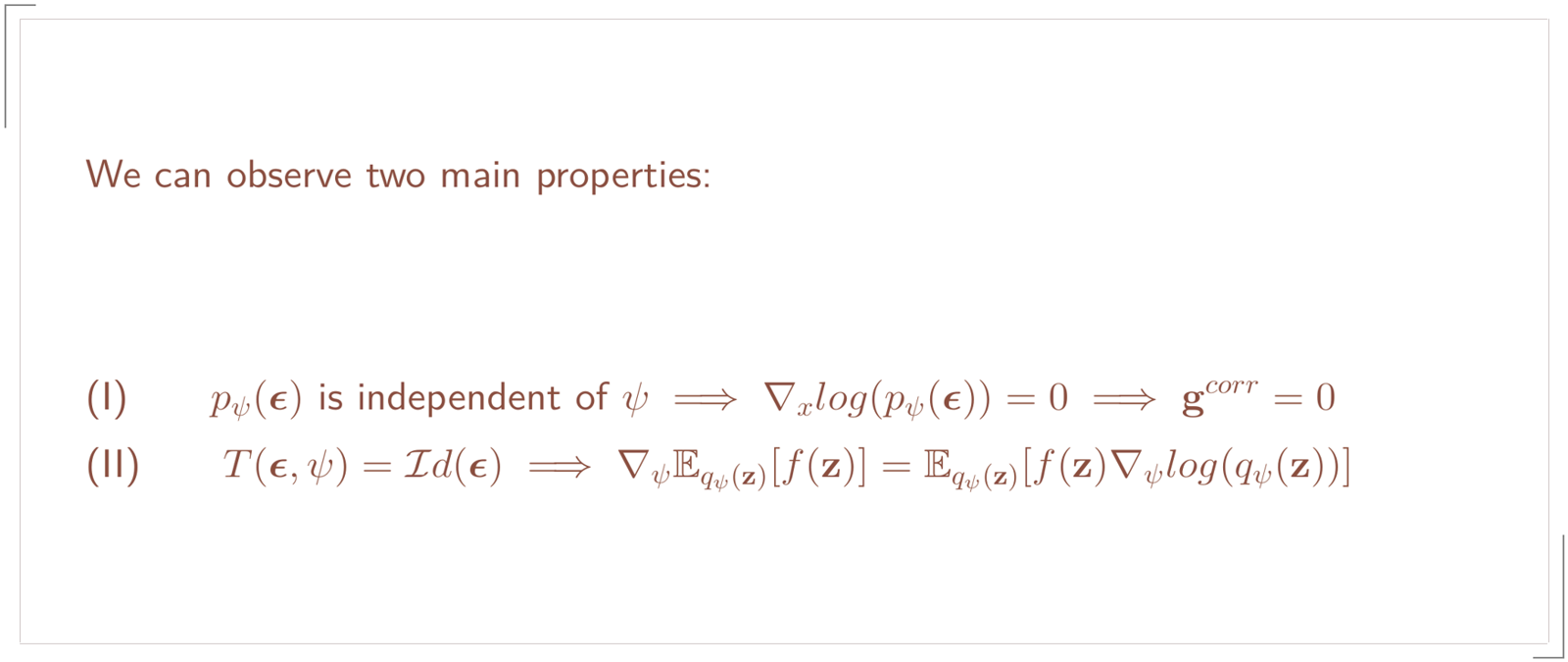

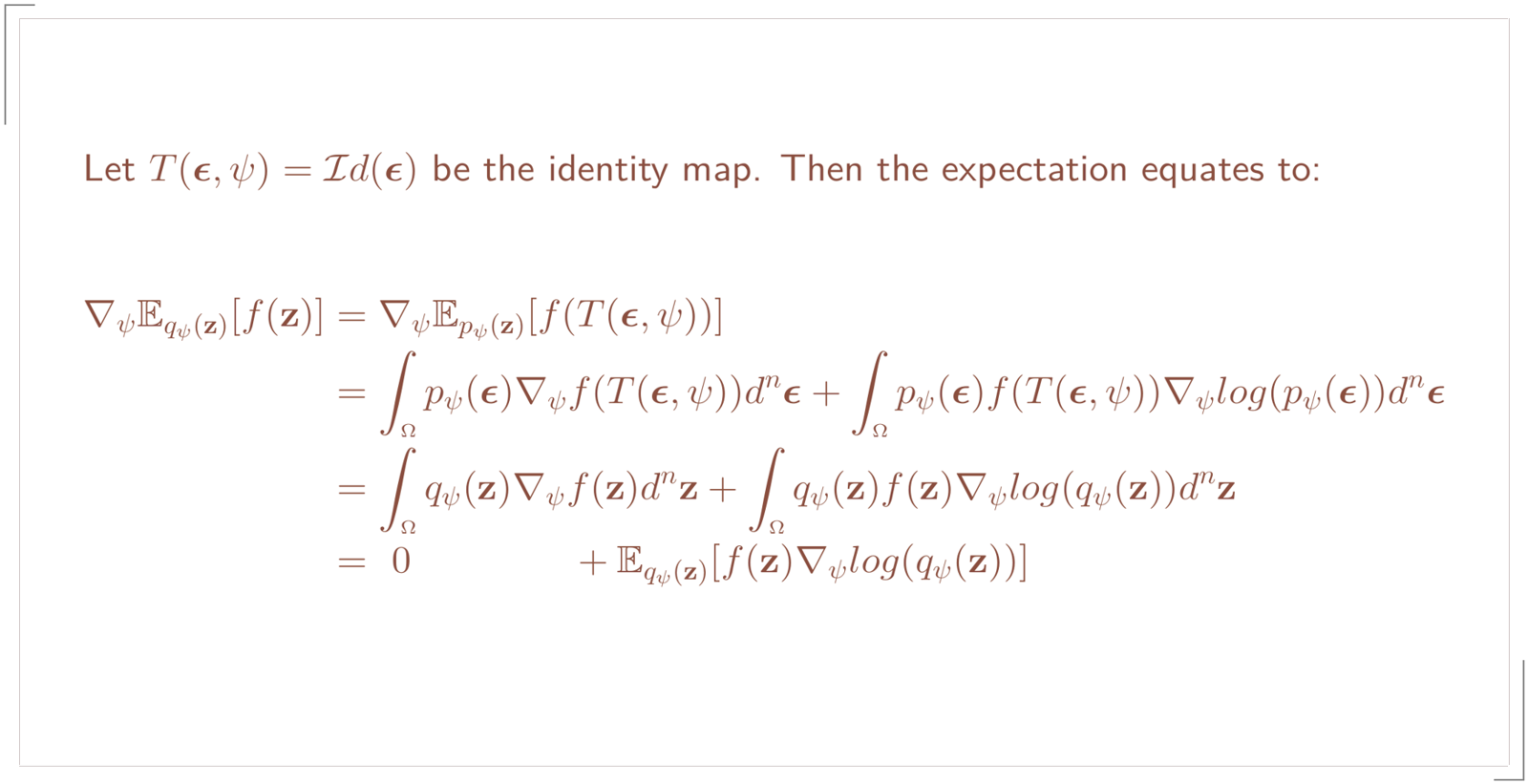

Due to the first property we can obtain the gradient of the reparameterized expectation. The latter property shows that we can retrieve the BBVI gradient when we choose T to be the identity.

Sources

[1] Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes by Diederik P. Kingma, Max Welling

[2] Variational Inference: A Review for Statisticians by David M. Blei

[3] The Generalized Reparameterization Gradient by Francisco J. R. Ruiz and David M. Blei

[4] Image Super-Resolution With Deep Variational Autoencoders by Darius Chira, Ilian Haralampiev

[5] Semi-supervised Deep Generative Models by Hao-Zhe Feng and Kezhi Kong

[6] An Introduction to Variational Autoencoders by Diederik P. Kingma, Max Welling